z

Inlay is a broad term describing techniques that are used to place varying material objects "within" a recessed negative space of a larger piece of material. The recessed space is referred to as a "pocket" (or cavity) in which the inlay rests. Generally, inlay is done in an artistic fashion, although techniques to achieve the final state are performed methodically, and most often the materials are leveled flush with each other to create a smooth, fluid surface.

Often, inlay is confused with "marquetry," which really is quite different in its complexity and construction, and has its own unique attention to detail. Marquetry is the application of thinly sliced pieces of wood veneer to create intricate patterns which are pieced together, and then glued ONTO the faces of wooden objects, typically covering the surface end to end for a seamless look. Inlay refers to materials of all kinds, which are set INTO a hollowed out cavity of a larger piece of varying or identical material.

One way to conceptualize these differences is to think of them as "onlay" and "inlay." Marquetry should be recognized as different from inlay, as it is an art form all its own and deserving of distinguishing regard.

History

Some of the earliest known pieces containing inlay are accredited to the region of Mesopotamia. The oldest known inlaid object is a limestone bowl with pieces of shell embedded into it that dates to 3,000 BC.

We also see inlay in many other ancient cultures, such as the Egyptian and early Chinese civilizations - specifically the Shang/Yin Dynasty (the oldest dynasty in Chinese history supported by archeological evidence).

The evolution of inlay through the ages, and its vast and varying applications is quite remarkable. From the Copper/Stone and Bronze ages, to the Baroque and Renaissance periods, the art of inlay has woven through so many cultures, leaving behind a trail of magnificent histories and heirlooms. Today inlay work continues to make its mark on modern day society.

Stages Of Construction

There are six key stages of inlay composition:

Creating the design

Cutting and crafting the parts and pieces that comprise the design

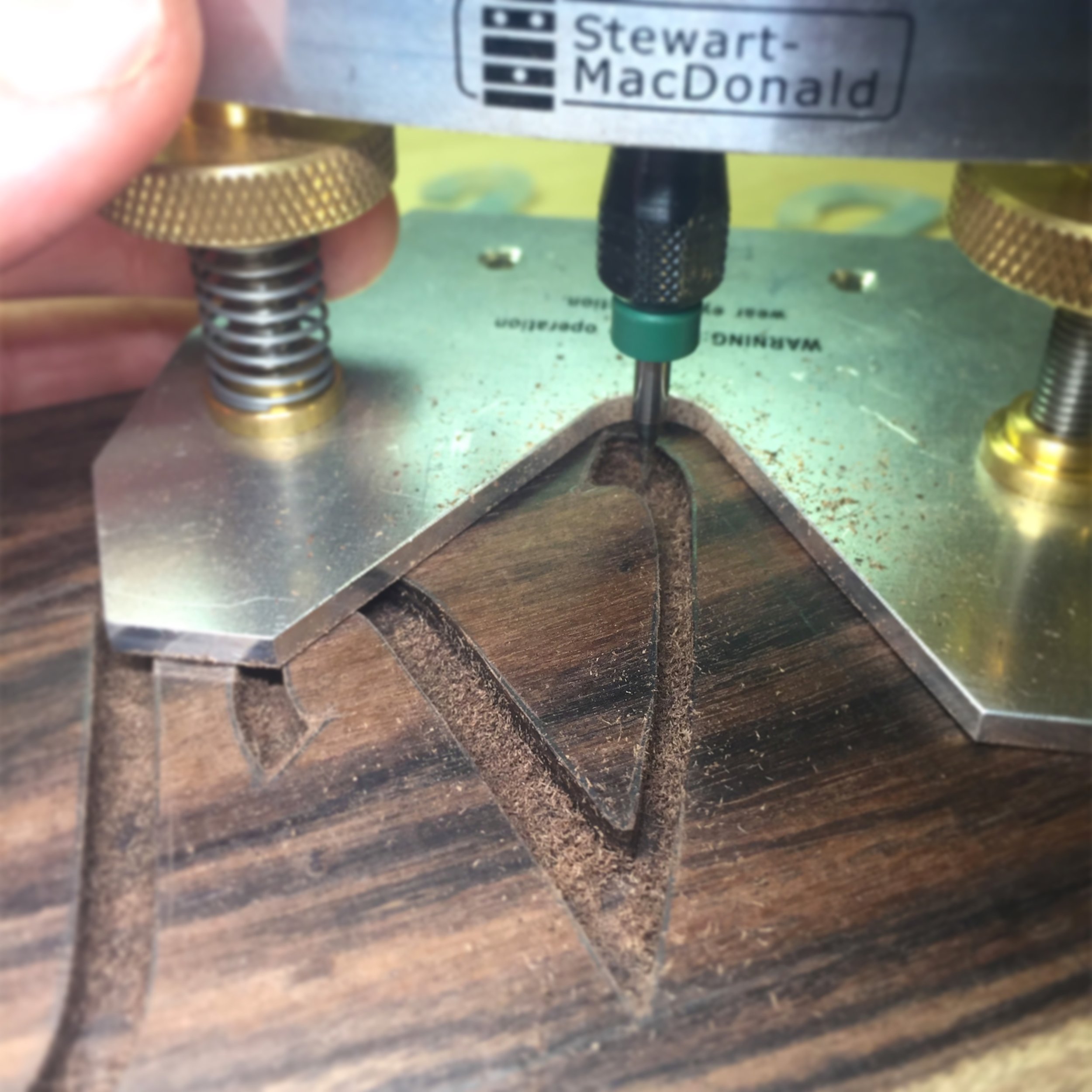

Routing the negative spaces (or pockets) where the inlay will be set

Setting and gluing the inlay into its pocket cavity

Leveling the inlay flush and smooth with the surrounding surface

Applying a finish or sealer

Cutting a pearl inlay by hand using a fret saw.

Routing a pocket by hand using a Dremel tool and router base attachment.

Inlay Materials

Inlay materials come in many forms and fashions. Most commonly, makers choose materials based on the overall look they want to achieve and the workability of the material (i.e. how hard or soft the material is, and how difficult it is to level flush).

Though any material can be used for inlay, certain materials are considered "tried and true" because they have been used for ages. You will find these materials in the list below:

Shell (abalone, paua, mother of pearl, sea snail, brown lip, etc.)

Metal (gold, silver, brass, copper, aluminum)

Stone (typically semi-precious or reconstituted)

Bone and tusk (materials primarily used in ancient civilizations)

Wood and veneer

Finely or coarsely ground material of many kinds, often used to fill an extra void (colored pebbles, granules, stone flakes, metallic dust, etc.)

Acrylic material (in endless colors & opacities, some even having a swirl or "tie-die" effect or even a shimmer or iridescence)

Example of inlay shell blanks - mother of pearl (top) with select figure, green abalone (middle), mother of pearl (bottom) with select color.

Understanding Shell and It’s Terminology

The descriptive terminology used for shell in the context of inlay is similar to some of the terminology used to describe wood. Abalone, for instance, has distinct “grain” and will occasionally have “knots,” similarly to a piece of wood. Pearl, for example, can boldly display very unique types of “figure.”

In woodworking, the term figure is used to characterize specific types of grain patterns that are occasionally found in certain wood species. Figure will always have a 3-dimensional aspect to its appearance, both on wood and shell. It will also have distinct, light reflecting qualities. Figured wood goes hand-in-hand with having a type of cat’s eye effect when you turn it in the light. This light reflecting visual phenomenon is called “chatoyance.” Chatoyance is also a term used in the classification of certain gemstones, for instance, and the way they reflect light (tiger’s eye or star sapphire, for example).

Pearl can be classified as having “figure” or “color” or both, and is graded for inlay (standard or select) by how intense these qualities are. Figured pearl is also identified by having a patterned 3-D effect. Often you see figured pearl having bubbly-like formations appearing on the surface, but the face is actually smooth to the touch. This is a variation of the optical phenomenon typical of figured material.

Pearl is also iridescent in its nature. Iridescence and chatoyance reflect light similarly, causing a visual illusion of positive and negative (light and dark) spots on the surface, often in a pattern, as the material is turned to angle the light, Iridescence differs from chatoyance because it reflects light with colors. Highly iridescent pearl will boldly display rainbows on its surface with a flashing effect as you turn it in the light. Chatoyance will also have this flashing effect, but without color.

Technology

Today woodworkers of all sorts receive help from Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines, for example, routers or lasers. Machines can be extremely useful in speeding up production time, which can, in turn, make products more available and affordable.

A machine such as a CNC laser can help an inlay artist tremendously, but not completely. Although the machine can cut the individual inlay parts, create the pocket cavity, and cut the final shape of a piece after it has been inlaid, the machine can do no more for the process. In fact, a CNC laser is not capable of cleanly cutting shell (such as abalone or pearl), which is often regarded as being among the most beautiful of inlay materials.

Even with a machine like a CNC laser (if you recall the numerous stages of the inlay process mentioned above) there is still an immense amount of work that can ONLY be done by hand. The maker still must join pieces by hand, glue and set them by hand, level them by hand, do any finishing touches by hand, and apply a finish or sealer by hand.

Example of a CNC Laser Machine.

While these machines enable an artist to work more quickly, they are simply additional tools in the maker's toolbox that can only produce art in the hands of the artist. There is a level of humble pride that exists alongside a maker and the work, one which can only be attained through the stages that are crafted by hand.